Природные опасности

Цунами

Подготовлен CERG — European Centre on Geomorphological Hazards — Strasbourg, France & the Editorial Board

Цунами (японское слово, означающее волна в гавани), одно из самых удивительных природных явлений, представляет собой серию океанских волн чрезвычайно большой длины, генерируемую в водоеме импульсным возмущением, которое перемещает воду. Цунами состоит из 5-6 волн, первая волна небольшая и называется нежной волной. Вторая и третья волны самые высокие и наиболее разрушительные.

Цунами (японское слово, означающее волна в гавани), одно из самых удивительных природы явлений, представляет собой серию океанских волн с чрезвычайно большой длиной волны и длительным периодом, создаваемым в толще воды импульсивным возмущением, которое вытесняет воду. Цунами состоит из 5-6 волн, первая волна которых мала и называется «мягкой волной». Вторая и третья волны — высокие волны и наиболее разрушительные.

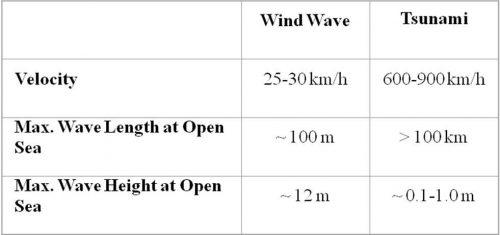

В море волны цунами менее 60 см высотой, даже не ощутимые с кораблей или самолетов. В тоже время, их длина часто составляет более 160 км, намного больше, чем глубина воды, по которой они движутся. Сравнение характеристик ветровых волн с волнами цунами приведено в таблице 1. Если глубина океана превышает 6000 м, незаметные волны цунами могут перемещаться со скоростью коммерческого реактивного самолета — более 800 км в час. Они могут перемещаться с одной стороны Тихого океана на другую менее чем за день. Эта высокая скорость делает важным определение цунами сразу же после его возникновения. Цунами перемещаются гораздо медленнее в более мелких прибрежных водах, поэтому высота волны начинают резко возрастать.

Generation of Tsunamis

Once the event which initiates the tsunami occurs the potential energy that results from pushing water above mean sea level is then transferred to horizontal propagation of the tsunami wave (kinetic energy). The return of the sea level to its normal position generates a series of waves propagating in all directions from the initially deformed area.

Propagation of Tsunamis The speed at which the tsunami travels depends on the water depth. If the water depth decreases, tsunami speed decreases. In the mid-Pacific, where the water depths reach 4.5 kilometers, tsunami speeds can be more than 900 kilometers per hour. Refraction and diffraction of waves are important to the tsunami propagation.

Refraction Consider progressive waves with wavelengths much larger than the water depths over which they propagate. These are called shallowwater or long waves. Because the waves are long, different parts of the wave might be over widely varying depths (especially in coastal areas) at a given instant. As depth determines the velocity of long waves, different parts travel with different velocities, causing the waves to bend, and this is called wave refraction. (Shallower the water depth, less is the velocity.)

Diffraction Diffraction can be considered as the bending of waves around objects. It is this kind of movement that allows waves to move past barriers into harbors as energy moves laterally along the crest of the wave. Offshore and coastal features can therefore determine the size and impact of tsunami waves. Reefs, bays, entrances to rivers, undersea features and the slope of the beach all help to modify the tsunami as it attacks the coastline. When the tsunami reaches the coast and moves inland, the water level can rise many meters. In extreme cases, water level has risen to more than 15 m for tsunamis of distant origin and over 30 m for tsunami waves generated near the earthquake’s epicenter. Since the first wave may not be the largest in the series of waves, one coastal community may see no damaging wave activity while in another nearby community destructive waves can be large and violent. The flooding can extend inland by 300 m or more, covering large expanses of land with water and debris.

Нет такого понятия, как типичное цунами, каждое из них отличается от других. Однако все цунами уникальны по количеству энергии, которую они содержат, огромную даже по сравнению с самыми мощными ветровыми волнами.

По механизмам генерации цунами можно классифицировать как генерируемые землетрясениями, извержением вулканов, образованием оползней или ударом (например, астероидов), вызвавшим цунами.

Они также могут быть классифицированы как отдаленные цунами и местные цунами в соответствии с расстоянием от прибрежной зоны, которая подверглась воздействию, до местоположения генерации.

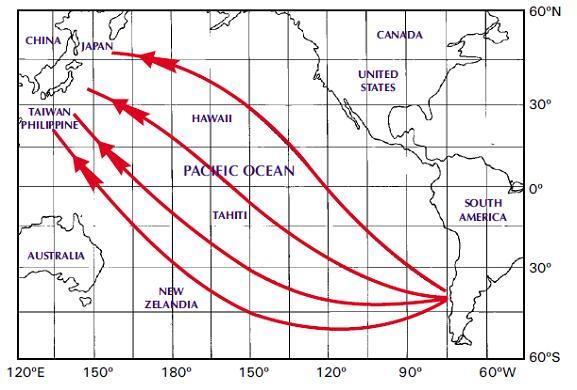

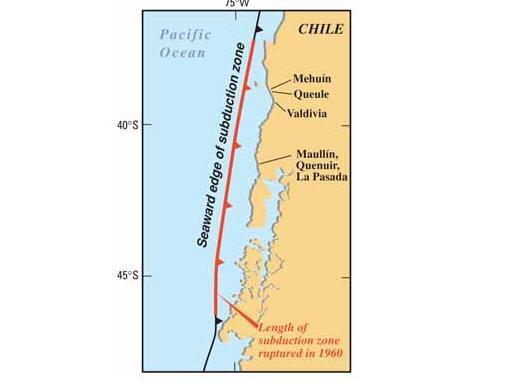

When a tsunami travels a long distance across the ocean, the sphericity of the Earth must be considered to determine the effects of the tsunami on a distant shoreline. Waves which diverge near their source will converge again at a point on the opposite side of the ocean. An example of this was the 1960 tsunami whose source was on the Chilean coastline, 39.5S., 74.5 W. The coast of japan lies between 30 and 45N. and about 135 to 140 E., a difference of 145 to 150 longitude from the source area. As a result of the convergence of unrefracted wave rays, the coast of japan suffered substantial damage and many deaths occurred.

As a tsunami approaches a coastline, the waves are modified by the various offshore and coastal features. Submerged ridges and reefs, the continental shelf, headlands, the shapes of bays, and the steepness of the beach slope may modify the wave height, cause wave resonance, reflect wave energy, and/or cause the waves to form bores which surge onto the shoreline.

Ocean ridges provide very little protection to a coastline. While some amount of the energy in a tsunami might reflect from the ridge, the major part of the energy will be transmitted across the ridge and onto the coastline. The 1960 tsunami which orignated along the coast of Chile is an example of this. That tsunami had large wave heights along the entire coast of Japan, including the islands of Shikoku and Kyushu which lie behind the South Honshu Ridge.

Locally generated Tsunamis

When a locally generated tsunami occurs, it impacts coastal areas a very short time after the event which produced the tsunami (earthquake, submarine volcanic eruption or landslide). Lapses as short as two minutes have been observed between the earthquake’s occurrence and the tsunami arrival to the closest shore. Because of this, a tsunami warning system is useless in this type of event and we should not expect instructions from an established system to react and keep us safe from the possible tsunami impact. This operation incapability of the warning systems is further increased by the communications and systems collapse generated by the earthquake. Hence, it is necessary to prepared in advance a proper response plan in case of a tsunami.

Импульсы, которые создают цунами, могут происходить из-за оползней, вулканов и ударов объектов из космоса (таких как метеориты, астероиды и кометы), но главным образом, это подводные землетрясения

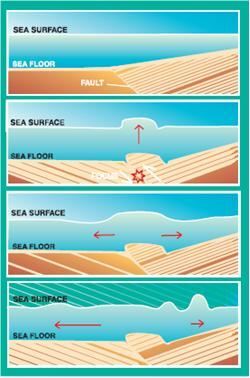

Возникновение цунами

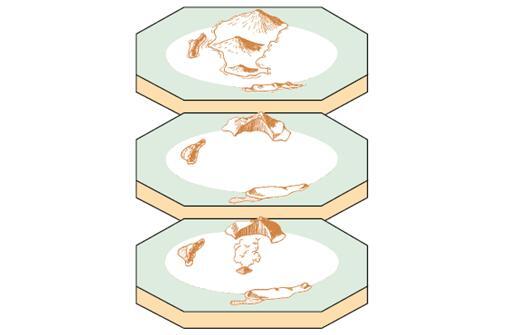

После того, как произойдет событие, которое инициирует цунами, потенциальная энергия, возникающая в результате поднятия воды выше среднего уровня моря, затем переносится на горизонтальное распространение волны цунами (кинетическая энергия). Возвращение уровня моря в его нормальное положение генерирует ряд волн, распространяющихся во всех направлениях от первоначально деформированной области.

Распространение цунами

Скорость перемещения цунами зависит от глубины воды. Если глубина воды уменьшается, скорость цунами уменьшается. В середине Тихого океана, где глубина воды достигает 4,5 километров, скорость цунами может составлять более 900 километров в час. Рефракция и дифракция волн также важны для распространения цунами.

ЦУНАМИ, ГЕНЕРИРУЕМЫЕ ЗЕМЛЕТРЯСЕНИЯМИ

Землетрясения, вызывающие цунами, возникают, когда морское дно резко деформируется и вытесняет вышележащую воду из своего положения равновесия (рис. 1). Однако не все землетрясения порождают цунами. Чтобы создать цунами, разлом, в которой происходит землетрясение, должен находиться под океаном или вблизи него и вызывать вертикальное перемещение морского дна (до нескольких метров) на большой площади (до ста тысяч квадратных километров). Мелкие очаговые землетрясения (с глубиной менее 70 км) вдоль зон субдукции (где океаническая плита скользит под континентальной плитой или другой более молодой океанической плитой) ответственны за большинство деструктивных цунами.

ЦУНАМИ, ГЕНЕРИРУЕМЫЕ ОПОЛЗНЯМИI

Оползни (как подводные, так и субаэральные), которые часто происходят во время большого землетрясения, также могут создать цунами. Во время подводного оползня равновесный уровень моря изменяется благодаря донным осадкам, движущимся вдоль морского дна.

ЦУНАМИ, ГЕНЕРИРУЕМЫЕ ИЗВЕРЖЕНИЯМИ ВУЛКАНОВ

Сильное извержение морских вулканов также может создать импульс, которая вытесняет водяной столб и создает цунами.

ЦУНАМИ, ГЕНЕРИРУЕМЫЕ УДАРОМ

К счастью, метеориты или астероиды очень редко достигают Земли. В современной истории не зарегистрирован астероид или метеорит, вызвавший цунами. Однако, поскольку существуют свидетельства падения метеоритов и астероидов на Земле, некоторые могли бы приземлиться в океанах и морях, поскольку 80% планеты покрыто водой. Их падение в океаны может вызвать гигантское цунами.

One of the most destructive tsunamis in recent history was generated along Chile’s coast by an earthquake in May 22, 1960 (Figure 2). Every coastal town between latitudes 36S and 44S was destroyed or severely damaged by the action of the tsunami and the earthquake. In Chile, the double combination of earthquake and tsunami produced more than 2,000 deaths, 3,000 injured, two million homeless, and damage worth $550 million (US). The tsunami caused 61 deaths in Hawaii, 20 in the Philippines, 3 in Okinawa, and more than 100 in Japan. The height of the waves ranged from 13 meters at Pitcairn Islands, 12 meters at Hilo, Hawaii, and 7 meters at several places in Japan, to minor oscillations in other areas.

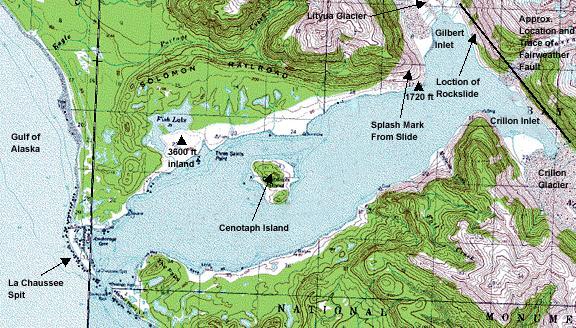

One of the most interesting landslide generated tsunamis happened in 1958 where about 81 million tones of ice and rock crashed into Lituya Bay, Alaska, Fifuren3). An earthquake had shaken the enormous mass loose. The landslide created a tsunami which sped across the bay. Waves splashed up to an astonishing height of 350 to 500 metres — the highest waves ever recorded. They scrubbed the mountain slope clean of all trees and shrubs. Miraculously, only two fishermen were killed.

In 1883, a series of volcanic eruptions at Krakatau in Indonesia created a powerful tsunami. As it rushed towards the islands of Java and Sumatra, it sank more than 5,000 boats and washed away many small islands. Waves as high as a 12-story buildings wiped out nearly 300 villages and killed more than 36,000 people. Scientist believe that the seismic waves traveled two or three times around the Earth.

In 1997, scientists discovered evidence of an asteroid with a four kilometre (2.5 mile) diameter that landed offshore of Chile approximately two million years ago, producing a huge tsunami that swept over portions of South America and Antarctica. Scientists have concluded that the impact of a moderately large asteroid, five to six kilometres (three to four miles) in diameter, falling between the Hawaiian islands and the west coast of North America would produce a tsunami that would attack cities on the west coasts of Canada, the United States and Mexico and would cover most of the inhabited coastal areas of the Hawaiian islands. (“Tsunami Teacher”, Educational material prepared by UNESCO-IOC www.unesco.org)

It has not happened, but conceivably, a tsunami could also be generated by very large nuclear explosions.

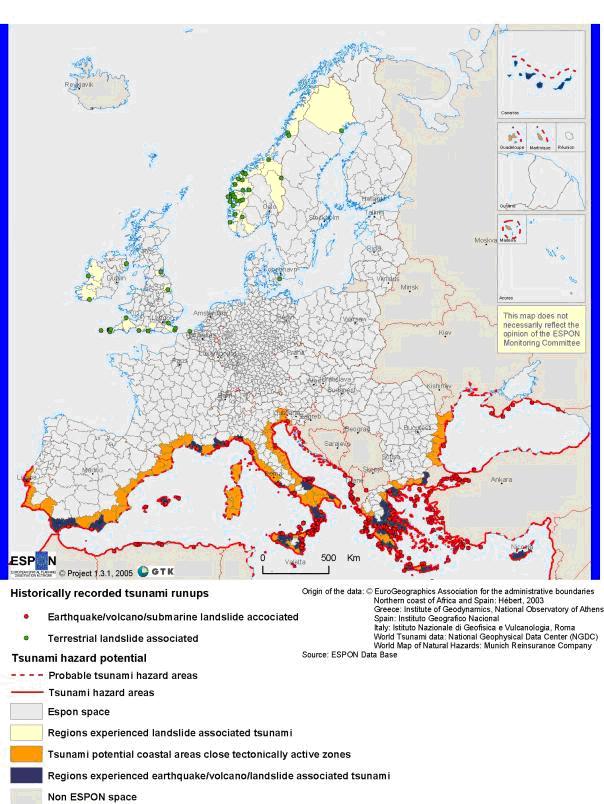

По данным Национального управления океанических и атмосферных исследований США (NOAA, www.noaa.gov), Тихий океан является наиболее активной зоной цунами. Но цунами были и в других водоемах, включая Карибское и Средиземное моря, Индийский и Атлантический океаны. В Северной Атлантике произошло цунами, связанное с землетрясением в Лиссабоне 1775 года, в результате которого погибло до 60 000 человек в Португалии, Испании и Северной Африке. Это землетрясение вызвало цунами до 7 метров в Карибском бассейне.

Карибский регион был поражен 37 наблюдаемыми цунами с 1498 года. Некоторые из них были произведены локально, а другие были результатом событий вдали, таких как землетрясение в Португалии. Количество погибших в результате этих цунами в Карибском бассейне составляет около 9 500 человек.

Средиземное, Черное и Красное моря также являются распространенными источниками цунами, вторыми после Тихого океана, с 98 наблюдаемыми цунами. Системы предупреждения о цунами в этом регионе должны учитывать местные цунами, которые ударят по побережью в течение нескольких минут. Возможно, самое известное цунами, хотя и не совсем подтверждено, связано с исчезновением острова Санторини в 1400 году до нашей эры, которое, по оценкам, вызвало 100 000 смертей.

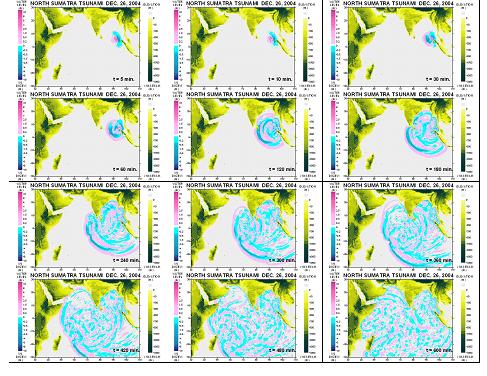

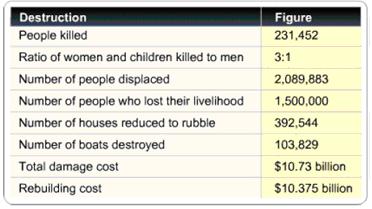

The devastating mega thrust earthquake (Indonesia/ Nicobar/ Andaman/ Sumatra Earthquake) of December 26, 2004, occurred on Sunday, December 26, 2004 at 00:58:53 GMT (7:58:53 AM local time at epicenter) with Mw=9.0 NEIC Epicenter Latitude 3.32 North, Longitude 95.85 East (USGS) or 3.09N, 94.26E southwest Banda Aceh in Northern Sumatra (Borrero, 2005). The earthquake has also triggered giant tsunami and the tsunami waves that propagated throughout the Indian Ocean and have caused extreme inundation and extensive damage, loss of property and life along the coasts of 12 surrounding counties in the Indian Ocean. The loss of lives has also been extended to the people from totally 27 countries from other parts of the world. (www.yalciner.metu.edu.tr/malaysia).

Разрушения, вызванные цунами, происходят главным образом от воздействия волн, наводнений, эрозии береговых линий, фундаментов зданий, мостов и дорог. Ущерб увеличивается за счет плавающих обломков, лодок и автомобилей, которые врезаются в здания. Сильные течения, иногда связанные с цунами, добавляют к разрушению, освобождая бревна, баржи и лодки на якоре. Дополнительный ущерб возникает в результате пожаров от разливов нефти, вызванных цунами, и загрязнения от сброшенных сточных вод и химических веществ. Приведенные выше последствия приводят к потерям жизней, социально-экономического, экологического и культурного потенциала.

| Country | Dead | Missing |

|---|---|---|

| Indonesia | 125,598 | 94,574 |

| Thailand | 5,395 | 3,001 |

| Sri Lanka | 30,957 | 5,637 |

| India | 10,749 | 5,640 |

| Myanmar | 61 | — |

| Maldives | 82 | 26 |

| Malaysia | 68 | — |

| Somalia | 298 | — |

| Tanzania | 10 | — |

| Bangladesh | 2 | — |

| Kenya | 1 | — |

| TOTAL | 173,221 | 108,878 |

There are three factors of destructions from tsunamis: inundation, wave impact on structures, and erosion. Agricultural areas are fully flooded and destroyed beyond recovery for many years to come. Strong, tsunami-induced currents lead to the erosion of foundations and the collapse of bridges and seawalls, infrastructures. Flotation and drag forces move houses and overturn railroad cars. Considerable damage is caused by the resultant floating debris, including boats and cars that become dangerous projectiles that may crash into buildings, break power lines, and may start fires. Fires from damaged ships in ports or from ruptured coastal oil storage tanks and refinery facilities can cause damage greater than that inflicted directly by the tsunami. Of increasing concern is the potential effect of tsunami draw down, when receding waters uncover cooling water intakes of nuclear power plants. For 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami total destruction figures are presented below:

Tsunami impacts on the environment in many ways, from the death of marine life to the destruction of livestock, plant life and the impact on geological features as well as damage to mangroves, coral reefs and vegetation. Of great concern are damage to marine habitats and the impacts on coastal towns that are intertwined with fragile marine systems.

Tsunami-induced environmental problems include:

- Ground water contamination.

- Damage to coral reefs, sea grass beds and mangrove ecosystems. o Salinisation of soils and damage to vegetation and crops.

- Tsunami-generated waste and debris. o Impacts on sewage collection and treatment systems.

- Damage to protected areas. o Coastline erosion and inundation.

- Changes in river hydrology.

- Loss of livelihoods based on natural resources or ecosystem services.

Archaeological sites, historical ruins, naturally beautiful places are lost under the impact of tsunami forces and due to inundation.

Да: в то время как эти стихийные бедствия не могут быть предотвращены, их результаты (например, гибель людей и потери имущества) могут быть уменьшены путем надлежащего планирования.

Однако для этого нужно хорошо понимать не только физическую природу явления и его проявления в каждой географической местности, но и совокупные физические, социальные и культурные факторы этой области. Некоторые из районов более уязвимы к цунами, чем другие. Поскольку частота цунами в Тихом океане высока, большинство усилий по управлению рисками сосредоточено в этой области мира. Независимо от того, насколько это район отдален, вероятность цунами следует учитывать при развитии управления прибрежными зонами и землепользовании.

В то время как определенная степень риска приемлема, правительственные учреждения должны способствовать развитию и росту населения в областях с большей безопасностью и меньшим потенциальным риском. Эти учреждения должны сформулировать правила землепользования для данной прибрежной зоны с учетом потенциального риска возникновения цунами, особенно если такая область, как известно, в прошлом понесла ущерб. Кроме того, следует избегать разрушения естественной растительности, такой как мангровые заросли, которые действуют как естественный барьер против цунами. Высокие здания в зонах повышенного риска увеличивают риск нанесения ущерба.

Системы раннего предупреждения цунами обнаруживают потенциально опасные землетрясения и могут обеспечить раннее предупреждение странам, которые могут пострадать. Координация этих глобальных систем предупреждения осуществляется Межправительственной океанографической комиссией ЮНЕСКО (МОК, http://www.ioc-tsunami.org) при поддержке Международного информационного центра по цунами. Основываясь на своем опыте в Тихоокеанском регионе, МОК также помогает создавать возможности предупреждения цунами в Индийском океане, Карибском бассейне, Атлантике и Средиземноморье.

Нет, поскольку порождающие цунами причины являются в основном естественными процессами, которые до настоящего времени не могут быть предсказаны, такими как землетрясения, оползни и извержения вулканов. Но, возможно, волны цунами могут быть вызваны очень мощными ядерными взрывами.

Учитывая нашу неспособность прогнозировать землетрясения и оползни (см. также модули землетрясений и оползней) и очень ограниченную способность прогнозировать извержения вулканов (см. модуль о вулканах), в настоящее время практически невозможно прогнозировать цунами.

Однако, глядя на прошлые цунами, ученые знают, где, вероятно, могут генерироваться цунами и потенциальные зоны воздействия. Эти потенциально опасные зоны связаны с геологически -активными зонами, которые имеют опасности землетрясений и извержения вулканов. Но не каждое землетрясение, извержение вулкана или оползень обязательно приводят к цунами. Прошлые измерения высоты цунами также полезны для прогнозирования будущих последствий цунами и ограничений затопления в конкретных прибрежных районах.

Мало что можно сделать для предотвращения возникновения стихийных бедствий (и, в частности, цунами). Но человечество научилось жить со всеми этими опасностями.

Надлежащее планирование защитных и предупредительных мер является ключевым фактором снижения потерь от этих природных опасностей. Современные защитные меры связаны прежде всего с использованием систем раннего предупреждения цунами с использованием передовых технологических инструментов для сбора данных и для сообщений о предупреждении. Такие страны, как Япония, Россия, Канада и Соединенные Штаты, разработали сложные системы предупреждения и взяли на себя ответственность за распространение предупреждающей информации другим странам.

В 1965 году Межправительственная океанографическая комиссия ЮНЕСКО (ЮНЕСКО / МОК) приняла предложение Соединенных Штатов расширить существующий центр цунами в Гонолулу, чтобы стать Центром предупреждения цунами в Тихоокеанском регионе (PTWC, http://ptwc.weather.gov/). Она также учредила Международную координационную группу (ICG/ITSU), впоследствии переименованную в Межправительственную координационную группу по Тихоокеанской системе предупреждения о цунами и смягчения их последствий (ICG/PTWS) и Международный информационный центр по цунами (ITIC, http: //itic.ioc- unesco.org/) для анализа деятельности Международной системы предупреждения о цунами для Тихоокеанского региона (ITWS).

Эта организация способствовала сотрудничеству на международном уровне и среди многих членов Тихоокеанского региона. ICG/PTWS проводит регулярные совещания для оценки деятельность его служб.

Для 46 государств-членов (по состоянию на май 2018 года) из Тихого океана и его морей, область ответственности PTWS включает Тихоокеанский регион, районы Южного океана в Тихом океане и все присоединенные моря, включая Филиппинское море, Восточно-Китайское море, Желтое море, Охотское море, Берингово море, Южно-Китайское море, Яванское море, Арафурское море, море Сулавеси, море Минданао, море Сулу, Целебесское море, море Бисмарка, Соломоново море, Коралловое море и Тасманово море.

Подобные системы предупреждения о цунами также существуют для Индийского океана (IOTWS) и Северо-Восточной Атлантики, Средиземного моря и его внутренних морей (ICG / NEAMTWS).

Одним из краеугольных камней смягчения последствий цунами является оценка опасности: посредством этого процесса выявляются уязвимые прибрежные районы и определяется потенциальный риск для людей, живущих там.

Ценность информации была проиллюстрирована во время цунами в Индийском океане. Большинство жертв не получили никакого предупреждения, но тысячи жизней были спасены в случае, когда знания о цунами использовались.

Эксперты утверждают, что системы предупреждения о цунами должны подкрепляться кампаниями по информированию общественности и планами реагирования на чрезвычайные ситуации, которые должны быть эффективными. Предупреждения мало полезны, если люди не знают, как реагировать на них. Знания становятся еще более критическими, если время предупреждения короткое или вообще нет предупреждения — в этом случае люди должны знать, как реагировать заранее.

Ценность знаний была продемонстрирована островитянами Симуне (Индонезия), которые потеряли только семь из их 78 000 жителей, хотя цунами 2004 года поразило их всего через восемь минут после землетрясения. Они держали в устной истории уроки цунами 1907 года (известные как «smong», что значит цунами на местном языке): островитяне точно знали, что делать, когда произошло цунами, в то время как популяции других близлежащих прибрежных районов были уничтожены.

A tsunami mitigation plan needs to:

- Quickly confirm potentially destructive tsunamis and reduce false alarms.

- Address local tsunami mitigation and the needs of coastal residents.

- Improve coordination and exchange of information to better utilize existing resources.

- Sustain support at state and local level for long-term tsunami hazard.

- Improve the awareness and preparedness of communities for tsunamis:

- Raise the awareness of affected populations.

- Supply tsunami evacuation maps.

- Improve tsunami warning systems.

- Incorporate tsunami planning into state and federal all-hazards mitigation programmes.

Civil defence authorities in each country can initiate public education programme consisting of seminars and workshops for responsible government officials, can publish informational booklets on the hazards of tsunami, and can co-ordinate with the communications media on the announcement of tsunami information. Other government agencies can take action also to mitigate future losses from tsunami. For example, government agencies can develop sound coastal management policies, which include zoning and planning for tsunami-prone coastal areas.

Internally, government agencies can streamline and co-ordinate their operating procedures and communications so they can perform efficiently when the tsunami threat arises. Procedures related to tsunami warnings should be reviewed frequently to define and determine better respective responsibilities between the different government agencies at all levels.

Scientific organizations can undertake research and engineering studies in developing evacuation zones or engineering guidelines for building coastal structures. Audio-visual materials can be prepared for educating children in schools and the public in general. Brochures and pamphlets can be printed describing the tsunami warning system and what the public can do in time of tsunami warning.

The natural environment can provide protection against tsunamis, and environmental destruction to make way for development can raise the tsunami risk of coastal communities. Tropical coastal ecosystems have sophisticated natural insurance mechanisms to help them survive the storm waves of typhoons and tsunamis such as coral reefs being equivalent of natural breakwaters causing waves to break offshore and allowing them to dissipate most of their destructive energy before reaching the shore.

Mangrove forests also act as natural shock absorbers, “soaking up destructive wave energy and buffering against erosion”. Systems of marshes, tidal inlets and mangrove channels also help limit the extent of inundation by floodwaters and enable flood waters to drain quickly.

Places that had healthy coral reefs and intact mangroves were far less badly hit than places where the reefs had been damaged and the mangroves ripped out and replaced by beachfront hotels and prawn farms during 2004 Tsunami.

However, there has been widespread destruction of natural coastal habitats to make way for urban development, population growth, industry, aquaculture, agriculture and tourism.

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF, http://www.worldwildlife.org) has recommended that tsunami mitigation strategies take into account:

- Rehabilitation and restoration of degraded coastal ecosystems that help protect from storm waves, especially coastal marshes and forests, mangroves and coral reefs.

- Adoption of integrated coastal zone management, including zoning and mandatory coastal setback. For example, hotels should not be built within a safety zone from the high tide mark.

- Strict enforcement of land and coastal-use planning and policies, including natural disaster risk assessments.

- Implementation of incentives to ensure that sensitive facilities are built away from high risk areas.

- Risk assessment that helps reduce the vulnerability of coastal development.

Осведомленность общественности о потенциальной угрозе цунами может быть достигнута посредством государственной образовательной программы, состоящей из семинаров и рабочих совещаний для ответственных государственных чиновников, информационных буклетов по опасностям цунами и что необходимо сделать в случае цунами.

- A strong earthquake felt in a low-lying coastal area is a natural warning of possible, immediate danger. Keep calm and quickly move to higher ground away from the coast.

- Tsunamis can occur at any time, day or night. They can travel up rivers and streams that lead to the ocean.

- A tsunami is not a single wave, but a series of waves. Stay out of danger until an «ALL CLEAR» is issued by a competent authority.

- Approaching tsunamis are sometimes heralded by noticeable rise or fall of coastal waters. This is nature’s tsunami warning and should be heeded.

- A small tsunami at one beach can be a giant a few miles away. Do not let modest size of one make you lose respect for all.

- Sooner or later, tsunamis visit every coastline around the ocean.

- All tsunamis, like hurricanes, are potentially dangerous even though they may not damage every coastline they strike. • Never go down to the beach to watch for a tsunami! • WHEN YOU CAN SEE THE WAVE YOU ARE TOO CLOSE TO ESCAPE.

- Tsunamis can move faster than a person can run!

- During a tsunami emergency, your local emergency management office, police, fire and other emergency organizations will try to save your life. Give them your fullest cooperation.

- Homes and other buildings located in low lying coastal areas are not safe. Do NOT stay in such buildings if there is a tsunami warning.

- The upper floors of high, multi-story, reinforced concrete hotels can provide refuge if there is no time to quickly move inland or to higher ground.

- Stay tuned to your local radio, marine radio, NOAA Weather Radio, or television stations during a tsunami emergency — bulletins issued through your local emergency management office and National Weather Service offices can save your life.

- Since tsunami wave activity is imperceptible in the open ocean, do not return to port if you are at sea and a tsunami warning has been issued for your area. Tsunamis can cause rapid changes in water level and unpredictable dangerous currents in harbours and ports.

- If there is time to move your boat or ship from port to deep water (after a tsunami warning has been issued), you should weigh the following considerations:

- Most large harbors and ports are under the control of a harbor authority and/or a vessel traffic system. Keep in contact with the authorities should a forced movement of vessel be directed.

- Smaller ports may not be under the control of a harbor authority. If you are aware there is a tsunami warning and you have time to move your vessel to deep water, then you may want to do so in an orderly manner, in consideration of other vessels.

- Damaging wave activity and unpredictable currents can affect harbors for a period of time following the initial tsunami impact on the coast. Contact the harbor authority before returning to port making sure to verify that conditions in the harbor are safe for navigation and berthing.

В то время как одно прибрежное сообщество может не испытывать никаких разрушительных последствий от цунами, другое близкое к нему сообщество может подвергнуться жестокому опустошению.

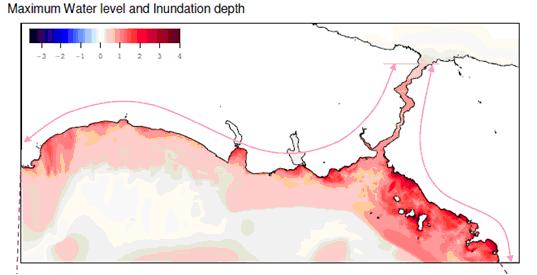

Компьютерное моделирование потенциального затопления цунами — горизонтальное внутреннее проникновение волн с береговой линии — может выявлять районы, которые, вероятно, будут затоплены во время цунами (позволяющее создавать карты опасности / уязвимости), и давать информацию о том, какие маршруты люди могут использовать для достижения предварительного определенных безопасных зон (используемых для разработки карт эвакуации).

Карты, обозначающие зоны затопления цунами — районы, которые могут быть затоплены большими волнами, могут помочь планировщикам и лицам, принимающим решения, в определении зон эвакуации и безопасных маршрутов.

Для этого наблюдения за результатами прошлых событий необходимы для проверки карт наводнения, полученных на основе моделирования.

One of the key tools for tsunami mitigation is the study and production of hazard maps of local coastal areas to ascertain how vulnerable they are to tsunamis – this can vary greatly along shorelines depending on the intensity of the waves, undersea features and the topographical lay of the land.

Hazard maps require knowledge of the historical tsunami record in order to estimate the probability that a tsunami will occur in the future. An integral part of emergency preparedness is understanding the tsunami hazard or threat. Since earthquakes are the most probable source, seismic hazard maps are needed to identify the potential earthquake source zones. In the case of tsunamis, this also includes trying to predict the potential height of waves.

In high-risk areas where the maximum potential source of a tsunami is known – for example if there is an active earthquake subduction zone offshore – tsunami generation, propagation and run-up can be mathematically modelled and wave heights estimated. Also, historical records of previous tsunamis charting earthquake magnitudes, and wave heights and run-up and inundation patterns, can be used to support tsunami hazard predictions.

One such study as outlined previously was performed for Istanbul, Turkey (Figure 1). Comprehensive tsunami simulations were based on 49 different scenarios considering not only active faults but also submarine landslide induced tsunamis by using OIC, a widely accepted, scientifically verified tsunami simulation code TUNAMI N2. The animations of the selected scenarios have been prepared by METU, The Department of Civil Engineering, Ocean Engineering Research Center using the tsunami simulation and visualization code NAMI DANCE, which has been developed for tsunami numerical modeling and simulations by Profs..Nobuo Shuto and Fumihiko Imamura in Tohoku University Japan. TUNAMI N2 determines the tsunami source characteristics from earthquake rupture characteristics. It computes all necessary parameters of tsunami behavior in shallow water and in the inundation zone allowing for a better understanding of the effect of tsunamis according to bathymetric and topographical conditions. For further information, http://yalciner.ce.metu.edu.tr/marmara/index_eng.htm

Tectonically induced tsunamis occur in Europe mainly in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. There are several geological and historical records of tsunamis (see above). The most endangered zones lie in close vicinity to the main volcanoes or along seismically active zones. Tsunamis caused by (submarine) landslides have mainly occurred in Norway, but also in some other areas in Europe (Figure 1). Often it is difficult to distinguish if an earthquake caused a tsunami or if an earthquake triggered a (submarine) landslide that then caused a tsunami. In general it can be concluded that tsunamis are possible along all shorelines that lie in tectonically active zones and/or in areas where (submarine) landslides are possible. Even though no devastating tsunamis have occurred in Europe in the last 100 years, the potential hazard is still high. (http://www.gsf.fi/projects/espon/Tsunamis.htm)